âHolding my breathâ: Rep. Jerry Carl frets over fate of congressional district

U.S. Rep. Jerry Carl said Wednesday he “didn’t like what he saw” from a Monday federal court review critical of Alabama’s new congressional map that maintains Mobile and Baldwin counties within his 1st congressional district.

Carl said he was “holding my breath” as the redrawn map gets a second review by a panel of three federal judges. The judges, during Monday’s hearing in Birmingham, questioned if the state was deliberately disregarding the court’s directive to create a second-majority Black congressional district.

It’s a high stakes battle that could alter the district that Carl has represented since 2021. At issue if whether Mobile and fast-growing Baldwin counties should be split for the first time in about 50 years.

“It’s the worst-case scenario in my mind,” Carl said. “We hope it doesn’t come to that.”

That possibility looms. An alternative map, pitched by the plaintiffs in the lawsuit challenging the state’s original congressional map, splits the two coastal counties and carves through Mobile.

The congressman addressed redistricting, and the state’s congressional map that remains in legal limbo during separate appearances in the two counties on Wednesday.

“I think anything is possible,” Carl said before a group of mayors and state lawmakers at a luncheon hosted by the Alabama League of Municipalities in Spanish Fort.

Related content:

“I’m OK with the way it’s redrawn right now,” Carl told AL.com after a breakfast speech before the Mobile Chamber, referring to the new congressional map redrawn by the Republican-dominated state House and Senate last month.

Economic impact

That map keeps Mobile and Baldwin counties within the 1st congressional district as compact “communities of interest” based on their shared geography and economic ties to the Gulf Coasts.

But plaintiffs in the case argue the state’s redrawn map continues to violate federal court directives by not creating a second majority Black district. One of the plaintiffs in the case, Lakeisha Chestnut of Mobile, also argues that it’s not essential for Mobile and Baldwin counties to remain together within the same congressional district.

Saraland Mayor Howard Rubenstein speaks at a luncheon hosted by the Alabama League of Municipalities on Wednesday, August 16, 2023, at Ralph & Kacoo’s in Spanish Fort, Ala. (John Sharp/[email protected]).

“I am concerned over the map drawers splitting Mobile and Baldwin,” said Saraland Mayor Howard Rubenstein, during the League of Municipalities luncheon. “We worked for the last 30 years to get a unified working economic partnership going in this area. I think just taking a line through it could really hurt us economically.”

Carl said he has the same concerns, noting that he recently spoke before a group of approximately 100 engineers who work at the Airbus manufacturing complex in Mobile. He said of those 100, approximately half lived outside of Mobile County.

“When you look at Airbus and Austal, not only would those 50 percent I no longer be able to represent, but Austal and Airbus would fall into a (Congressional) District 2 where the lines are drawn,” Carl said. “It will flip everything upside down.”

He added, “If you get into District 2, you will get a representative from Montgomery who will represent your city in Washington. We fight for money constantly … to get (Department of Transportation) money for the area, and any money we can. The idea of your city fighting for money (with) Montgomery is not a good scenario at all.”

Racial splits

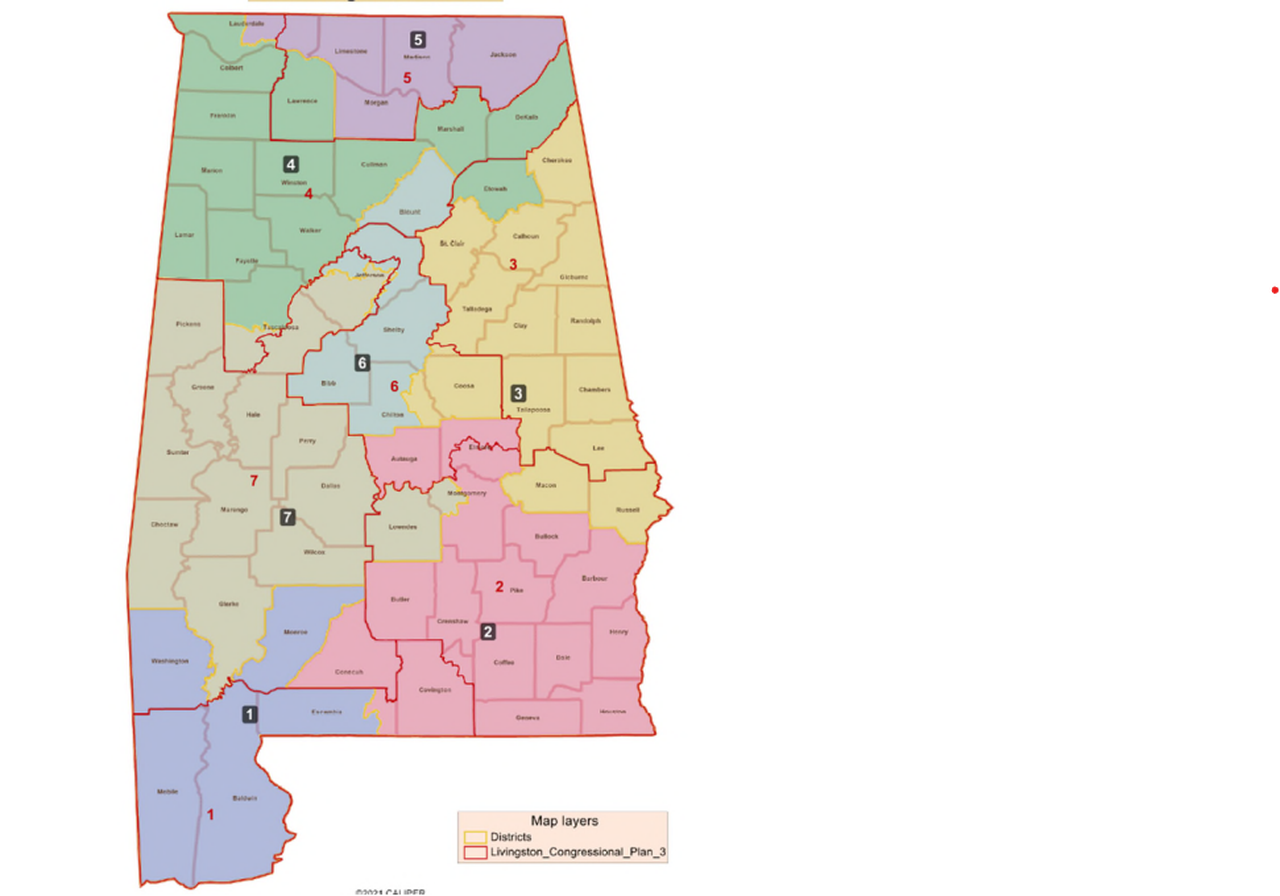

Alabama’s 2021 congressional district map, with the new 2023 map superimposed with red lines. The Supreme Court ruled the 2021 map likely violated the Voting Rights Act. A three-judge court will decide whether the 2023 map fixed the problem. (Image is from court brief by lawyers for the state).

The comments come after a three-judge federal panel criticized the state’s revised map on Monday for not creating a second majority Black district. That same panel ruled against the initial Alabama congressional map as a violation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 because it prevented Black voters from electing a candidate of their choice.

Alabama was forced to redraw its congressional map after the U.S. Supreme Court, in a surprising move in June, upheld the panel’s findings. The high court agreed that Alabama, with just one majority Black district out of seven in a state with one-fourth of its residents Black, likely violated federal law.

All three judges, during Monday’s proceedings in Birmingham, asked the state’s lawyers whether Alabama was ignoring their findings when they did not create a second majority Black district. The Alabama Legislature redrew the map during a special legislative session that concluded with Gov. Kay Ivey approving the map on July 21.

The latest map leaves District 7 – currently represented by the state’s lone Democratic member of Congress, Rep. Terri Sewell of Birmingham – with a Black voting age population of 51%. That is down from 55% in the previous map.

A line of people wait outside the federal courthouse in Birmingham, Ala., on Monday, Aug. 14, 2023. to watch the Aug. 14, 2023 hearing. A three-judge panel is reviewing Alabama’s new congressional districts. They will decide whether to let the map stand or step in and draw districts for the state. (AP Photo/Kim Chandler)AP

The new map’s next highest proportion of Black voters is within the redrawn District 2, which covers Southeast Alabama. The new map increases that district’s Black voting population from around 32% to 40%, an increase that civil rights groups say is not enough to give Black voters an opportunity to elect a candidate of their choosing.

Carl said he was frustrated with the focus on racial demographics determining the outcome of congressional redistricting and “federal programs” in general.

He said he believes federal law “was never about a majority” of Black voters, but to create a congressional district that was “leaning” toward the possibility of giving a Black candidate a chance at winning.

“The focus on Black majority districts … that’s not what the law says,” Carl said. “We’re trying to get away from racial and calling things by skin color. So many federal programs are determined by the color of your skin. I feel like that’s going back to the 60s.”

Edmund LaCour, Alabama’s solicitor general, has said the redrawn map was as “close as you get” toward creating a second majority-Black congressional district without violating the U.S. Constitution or traditional redistricting principles such as drawing compact districts.

The plaintiffs, including Chestnut of Mobile, argue that it’s possible to draw a map that includes two majority Black districts – even if means splitting the coastal counties.

If the court has the map redrawn, the possibility looms for splintering the two major counties of Alabama’s 1st congressional district for the first time since the 1970s.

Communities of interest

Alabama’s 1st congressional district currently includes Mobile, Baldwin, Washington, and Monroe counties as well as parts of Escambia County. The voting age population is 67% white and 25% Black, but most of those Black residents live in Mobile County.

The split of Mobile and Baldwin counties factored heavily into the Supreme Court’s written opinions in June, with Chief Justice John Roberts dismissing the concerns. Justice Clarence Thomas, however, said it was “indisputable” that the Gulf Coast region is a “community of interest.”

Roberts, writing for the Court, found that some region has to be split up so others can be united. He said that even if the Gulf Coast did constitute a community of interest, the plaintiffs’ maps would be considered “reasonably configured” because they joined a different community of interest called the “Black Belt.”

The two counties, while led mostly by Republicans, have different racial demographics.

Baldwin County, over the past 52 years since the 1970s Census, has grown over 314 percent. But it remains largely white, with the 2020 Census showing only 8.6% of the county’s population as Black.

The more urban Mobile County, by contrast, is 37% Black. The City of Mobile, itself, is over 52% Black and only 41.5% white.

Republicans have been reluctant in creating a Democratic-leaning district, punting the issue instead to the courts in hopes the state will win in a second round of appeals.

Carl said he anticipates the entire case returning to the Supreme Court for another consideration.

“Just give me the lines and tell me where I’m running,” Carl said. “I’m ready to go.”